Olympic Weightlifting - A Novice's Endeavor

Mobility and more power by cultivating movement efficiency and work capacity.

Austin Haedicke

1863 Words | Read Time: 8 Minutes, 28 Seconds

2023-12-23 06:38 -0800

Arguably, the snatch is the most powerful and athletic movement of all time; taking a barbell from the ground to overhead in single explosive movement. It is competitively performed in conjunction with the 2-stage clean-and-jerk.

These are known as the Olympic lifts. My original 12-week plan was interrupted by a rib injury in late summer, so I was left with 8-weeks and some change to see what I could accomplish never having done a dedicated Olympic program before.

Why (Olympic) Weightlifting?

Olympic weightlifting has many obvious benefits to grappling sports:

- compound, multi-joint movement

- explosive power

- kinesthetic awareness

- mobility / range of strength

In contrast to powerlifting (bench press, back squat, and deadlift), the Olympic movements (snatch and clean-and-jerk) require dynamic force application through a wide range of motion (mobility).

My initial interest was precisely this. “Movement” can be a significant limiting factor in capacity training. If you’re much less efficient at a more complex or more difficult movement then, as a result, energy efficiency and work “capacity” will suffer.

Third, they look freakin’ cool!

It’s a natural fit for me to wrap up the year addressing this movement / mobility weakness in a fashion that will also pay dividends to my grappling.

From the NonProphet Capacity Manual:

Generally, poor exercises are so because the player has made poor choices; most trainees have underprepared tissue and over-inflated confidence…Instead of thinking about exercises you want to do, think about attributes that the “pattern” offers. Consider how that pattern might transfer to your sport or your interest.

A study from 1980 estimated that during the drive portion of the jerk, 56 Kg lifters produced 2,140 watts and 110 Kg lifters produced 4,786 watts (ref.).

Those would be peak wattages, held only for a second or two, but still; were talking about 38 - 43 W/Kg. For reference, on the 300FY (a.k.a. 10 minute bike test) I scored about 5 W/Kg (average).

Thus we have a full-circle of expression:

- Power as “watts".”

- The ability to sustain power or resist fatigue as “capacity.”

- The ability to hold tension as “strength.”

- The ability to persist as “endurance.”

Books and Resources:

The above “bible” by Greg Everett (@catalystathletics) came highly recommended, however it truly is an encyclopedia. It’s not something you read once and “have it.” Rather, it’s something to refer back to over and over again. In that regard, it’s not a program in and of itself, and differs from the programs I’ve reviewed in the past.

Additionally, Squat University (@squat_university) and Zack Telander (@coach_zt) have an abundance of useful content on Instagram and YouTube.

Programming:

Recently, I published a piece emphasizing the importance of processes over prescriptions. For me, the first 4 weeks or so of any fitness program are usually highly experimental and subject to change — that is, they’re not a structured program yet.

It takes me 4 - 6 weeks to hit a wall and know what kind of volume I can handle in the weight room on top of my grappling training and how various intensities will effect me both acutely (day-to-day) and chronically (weeks-on-weeks).

This block was particularly difficult because I suffered a rib injury in the late summer which forestalled any heavy lifting. However, this actually turned out positive for learning the Olympic Lifts because I physically couldn’t rely on strength when initially exploring the movements.

The programs in Greg’s book follow a few stages that I’ve noticed myself:

- Developing GPP (general physical preparedness) with volume focused on non-dynamic support lifts (back squats, front squats, overhead squats, overhead presses) and light technical work (with a dowel rod or PVC).

- Learning “power” variations of the squat / full / competition lifts and develop a working understanding of relevant loads for your body, skill level, and each lift.

- Learning different combination lifts and how to diagnose and address different problems at different segments of each lift.

- Likely going back to the drawing board with Stage 1.

Each of my training sessions (about 3 / week) has followed a similar template based on my experience with NonProphet’s strength program and Dan John’s Easy Strength:

- General Warm Up: 10 minutes of Zone 2 (any movement)

- Specific Warm Up / Technical Progression

- Working Sets (less than 10 reps total per movement)

- Support / Supplemental Movements

- Mobility & Breath

Additionally, somewhere around 50 total reps / session (all sets x reps x movements combined) kept the sessions from getting too long and kept focus short.

My Process:

Reasonable starting programs from Greg’s book included:

- “Master’s Program”,

- “Simple 3-Day Split”, and

- “Lovel 0 Program.”

While GPP was farm from my issue, I had (and still have) some grave mobility and technical issues that need addressed. The greatly condensed and abridged “For Sports” variation of Greg’s book emphasizes that “in addition to sport-specific training athletes may not have time to dedicate to developing the mobility required for the full (squat) variations of the lifts, but would still benefit from the power variations.”

Competency with the clean came relatively quickly and I adapted my training split to focus on the snatch two days / week and the clean one day. As progress continued, I moved to a 3-day split consisting of:

- Snatch / variations

- Clean & Jerk

- Jerk / variations

For me, the snatch was perennially frustrating, complicated, and required a continual renewal of humility. As one segment of the lift would improve, another would seemingly have the wheels fall off.

To me, this highlighted Greg’s emphasis that the inexperienced lifter isn’t capable of “trusting their intuition” — because it hasn’t been developed or calibrated — regarding programming.

For example, I became wed to certain snatch-variant combinations rather than actually addressing what parts of the lift I needed to work on. Obviously, learning to spot errors and then correct them are separate skills.

Quite literally I should have been following a structure similar to this 62 year old beast:

A post shared by @ginalapertosa

I don’t necessarily think this was a mistake though. I was just so technically maladapted that it took 8-weeks for me to work up to the recommended starting weight of 50% body weight for snatch exercises. The catch-22 is that a lighter weight allows for a successful lift with sub-par technique and bad habits getting reinforced, while a heavier load might result in a missed lift and you still haven’t learned anything.

Lessons Learned (So Far):

I was relieved to hear Zach Telander talk about his 7-year journey from zero-to-hero (315 lbs snatch at about 230 lbs). That’s a comparable timeframe to earning a black belt. So, this has been a humbling experience to say the least; to remember how frustrating it is to start from nothing and try to learn everything all over, all at once.

Here are some notes I collected to remind myself of in the future:

Junk Mobility:

Even under the guise of “addressing limitations” in this training block, I avoided the hard work I needed. Deadhangs and hamstring stretches were “a good hurt.” What I really need though was “more time in the hole.” Deep squats. Specifically pushing my knees apart and flattening my back.

The Seduction of the Power Meter (during warm ups):

Who brags about how hard they can go in a warm up? People who aren’t very smart. Yet, the power meter (watts or RPMs) are a surefire way to be beholden to an external metric which is counterintuitive to a proper warm up’s goal of assessing your internal state. Take your shirt off and cover the dial. Set a timer on your watch. Use your breath as cadence.

Fewer Reps, Longer Rests:

Similar to the warm up seduction, fewer reps can incline one to increase load prematurely. When doing combination lifts (which compound the reps / set) fatigue becomes a limiting factor rather than technical efficiency. Additionally, it’s more difficult to assess where / how you went wrong (or right) on a set of 5 rather than a set of 1 or 2.

Likewise, in order to keep fatigue from being a limiting factor and allowing yourself to learn, long (I mean 5 minutes or more) rests may be needed between sets.

Conservative Breathwork:

I’ve found out the hard way, many times now unfortunately, that your palette is a sensitive muscle. The point of post-training breathwork is to jump start recovery by down-regulating your nervous system. It’s again counterintuitive to make this a stressful process by trying to impose an arbitrary cadence. You certainly can and will tear your palette if you’re determined to not listen to your body — I have several times.

Better Programming:

Humans learn better sequentially rather than concurrently. It’s more efficient to become fluent in English and then Spanish rather than learn what “dog” means in several languages first. Likewise, it probably would have been better to focus on a single lift rather than all three. For example, 3 days of cleans until they were proficient, then adding jerks for 2 / 3 days, then later switching to 2 C&J days and 1 snatch day, etc.

Accessory / Support Lifts:

This was a difficult balance to strike as well. Early on I wanted to emphasize “doing the thing” so support lifts seemed like a less than ideal use of time. Partially, this perception was skewed by inexperience, but also by my inefficiency at the movements themselves — a few reps were much more taxing than they should have been.

However, similar to “junk mobility” above, spending too much time banging my head against the wall and reinforcing bad technique; the tempo overhead and front squats that I later added would have likely been more efficacious than “just stretching.”

Going Forward:

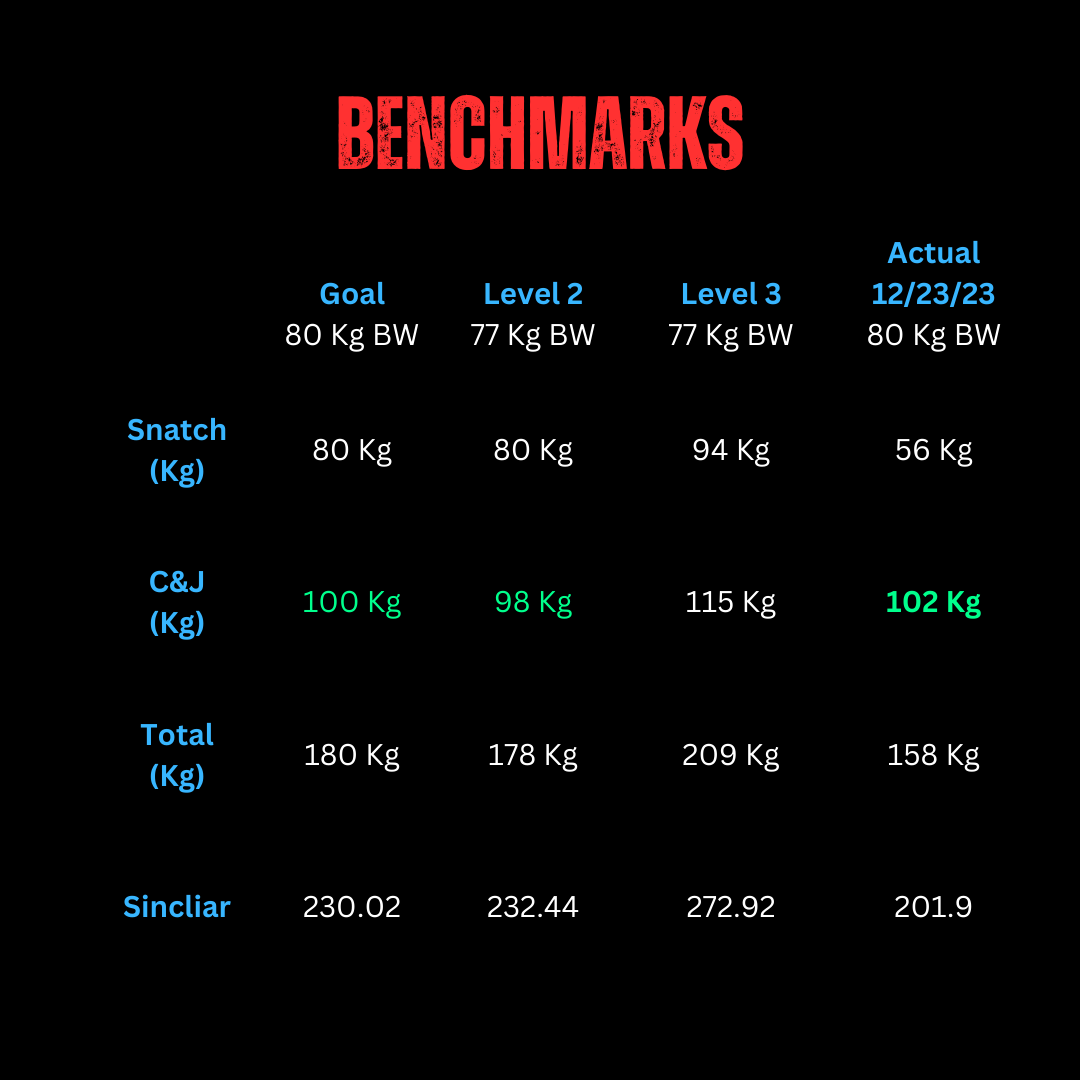

At the outset I had ambitious goals of wanting to achieve a 2.25x bodyweight total (180 Kg / 395 lbs) — that’s the combination of your snatch and clean-and-jerk 1RMs. This would have put me at Greg’s “Level 2” or “lower intermediate” skill level.

The conundrum I find myself in is that I don’t have time to be great at everything (and neither do you). So, I must choose, not compromise, but make an informed decision and accept the consequences. What shall we pursue? What shell we include, and at the exclusion of what?

For example, Peter Attia recommends 2 - 4 hours of Zone 2 training / week (ref.). I spend about 6 hours / week on the matts and another 4-6 hours / week on strength and conditioning. Whilst Zone 2 is a great foundation and lever for longevity (as is Peter’s interest), it is arguably the physical domain with the least carry over to grappling (I didn’t day none!) (ref., ref., ref.).

That title belongs to capacity training, specifically recoverability (i.e. interval weight training or multiple rounds of multiple energy systems). I do plan to continue to develop my Olympic Weightlifting because of it’s high transferability to grappling and implications for capacity training.

However, the extent and volume remains uncertain. I plan to re-enroll in the Space Program’s 6-week Escape Velocity program to further explore, understand, and assess my individual and sport-specific needs.

Olympic lifting may be becoming as beloved a staple as an Assault Bike is begrudging.