Deep breathing practice facilitates retention of newly learned motor skills

Yadav & Mutha - Scientific Reports - deep breathing benefits, motor memory enhancement, meditation and memory, motor skill retention, neuromotor rehabilitation, cognitive enhancement techniques.

Austin Haedicke

1200 Words | Read Time: 5 Minutes, 27 Seconds

2024-01-26 06:01 -0800

Have you ever been to a combat sport practice where the “warm up” runs you ragged before the technique portion of the class? This is a fantastic article that illustrates why that is a very bad idea. The brain needs to be in a relaxed state in order to maximize learning — motor / movement learning is not different from cognitive / academic learning in this regard.

In this study, a group of 40 right-handed subjects (control group x14, breathing-immediate group x16, breathing-late group x10) were instructed to trace a perfect circle (learning) and then asked to repeat the drawing (test).

The expermimental (breathing) groups were asked to complete a 30-minute session of alternate nostril breathing (8-10 breaths / minute) either immediately after the learning portion of the experiment (breathing-immediate group) or 30 minutes later (breathing-late group).

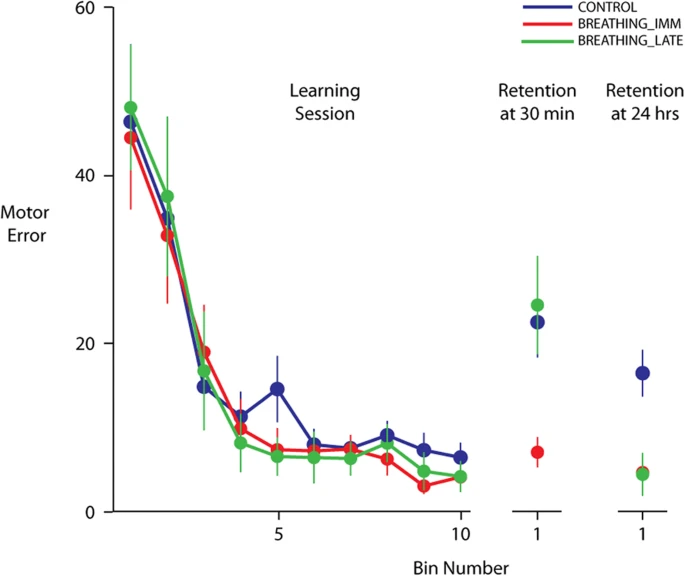

“The breathing-practice group retained the motor skill strikingly better than controls, both immediately after the breathing session and also at 24 hours.”

More specifically, the breathing-late group conducted their intervention (breath practice) after the first retention test at 30 minutes. Notably, the breathing-late group did not perform as well as the breathing-immediate group on the 30-minute test, but they outperformed that control group on the 24-hour test.

The graphic above also shows us, importantly, that the number of tracing errors was quite high in the beginning and that it rapidly decreased in 5 training sessions. The reduction in errors continued, but at a much slower rate, from the 5th to the 10th training / learning session.

We can also see that the standard deviation / margin of error (the “whiskers” with the dots) also greatly reduced as the learning sessions progressed

“Our results thus uncover for the first time remarkable facilitatory effects of simple breathing practices on complex functions such as motor memory, and have important implications for sports training and neuromotor rehabilitation in which better retention of learned motor skills is highly desireable.”

Yadav, G., Mutha, P. Deep Breathing Practice Facilitates Retention of Newly Learned Motor Skills. Sci Rep 6, 37069 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1038/srep37069

When we are stressed, that is our sympathetic nervous system is highly activated, we do not learn well because our biology is in a panicked survival state. This is true regardless if you identify with the emotional state of “feeling stressed” or not; your biology doesn’t care whether you “feel stressed” or not. If you’re in a hurry, always on the go, you’re engaging in a more sympathetic state of being.

The specific breath protocol used for this study was a 30-minute intervention where subjects were queued by a auditory tone to inhale, hold, and exhale for 2, 2, and 4 seconds respectively. After each breath cycle, the participants would switch nostrils, blocking the closed nostril with their finger. So, the protocl looke like this:

- Inhale 2 seconds (left nostirl)

- Hold 2 seconds (left nostril)

- Exhale 4 seconds (right nostril)

- Inhale 2 seconds (right nostril)

- Hold 2 seconds (right nostril)

- Exhale 4 seconds (left nostril)

There are several important regulatory factors for this practice. First, it is simple, which increases adherence and reduces errors imposed by more complex protocols. Second, all breaths are done through the nose, which is a parasympathetic signal compared to the sympathetic / arousal signal of mouth breathing.

Third, the exhale is the longest portion of the breath cycle which is another down-regulatory factor; contrasted with holds (which are a stress signal) and inhales (which are up-regulatory signal). Fourth, alternating nostrils proivides bi-lateral stimulation — a similar process that is used in EMDR treatment for PTSD (ref.).

Once again, when our brain is in a “traumatic” or “stressed” state, those states are anti-thetical to learning. Training is not performance. Survival is not growth. Testing is not learning; lest the test is a poor indicator of performance.

What does this mean for sports training, be that grappling, striking, golf, or football? While various sports have different degrees of technical, pysical, and psychological facets, they all require motor skills (bodily movement) to be applied — usually under a very specific context (e.g. rules of the game).

Using grappling as an example, tyically you go to class, are shown a couple techniques, do some positional or open sparring then go home. A similar protocol us often used in other “ball sports” — you warm up, learn something, then try to practice it, and maybe do some rote conditioning work.

When you leave practice, you probably do nothing on the car ride home, when you could be doing something intentional to benefit your performance (e.g. remembering what you learned in class, just like the study participants drawing a circle).

You could take an extra 5-10 minutes at the end of a 3-hour practice to do your breath practice, or do it on the carride home, or even wait until you get home. Rembmer, in the study the breathing-late group still outperformed the control group the next day (24-hours later).

If we really dig in, we need to inquire about the role of “drilling” and how / if “the number of repetitions” matters. This is highly related to the question of block vs. random practice:

What we can learn about this topic from the article I’m reviewing here is that:

- Yes, repetitions matter. We do need to “practice” and do the thing to learn.

- The number of practice sessions and volume of repetitions greatly reduces the chances of error if those repetitions are done precisely and intentionally — avoiding “junk volume.”

The reason the standard error discussion is necessary is becasue we can have some highly skewed confirmations biases. For example, obviously, generally the more you practice something the better you get at it. This is particularly true in the short-term — so called rapid “beginner gains.”

The problem is that we can get really good at taking a test and therefore the test’s arbitrary score or result fails to become an accurate indicator of what it is supposed to be measuring. Relevance becomes lost. For example, the NFL combine is a notoriously poor indicator of actual career player performance (ref.). This brings us full circle to the points Trevor makes in the video above.

This is also closely related to the difference between the test — in the study we’re reviewing — measuring a learner’s retention or being counted a training (re-learning) session in itself. Hence the value, in grappling terms, of “positional” or “specific sparring” — where a measured and controlled degree of randomness and resistance variables are introduced. Too many variables equals too much stress, and too much stress (literally) shuts down learning.

“In general however, retention, when assessed over an entire session that also involves additional practice, must be interpreted with caution because performance beyond the first few trials also includes the effects of re-learning. Early performance, such as that seen during the first bin in our case for example, may be a better indicator of retention in such cases.”

In summary, this article gives fantastic insight in to how we can improve our ability to learn new technical motor pattens whether it’s a passing route in football, and unfamiliar movement pattern or wall angle in climbing, or any number of technical configurations in combat sports.