Effects of mind body exercise on anxiety

Mental Health and Physical Activity, March 1, 2024

Austin Haedicke

1293 Words | Read Time: 5 Minutes, 52 Seconds

2024-05-05 06:01 -0700

Exercise reduces anxiety. However, there are some unique qualifiers and limitations observed in the literature that make this far from a panacea or a one-size-fits-all solution where “it just works and more is always better.”

Photo by Taylor Deas-Melesh on Unsplash

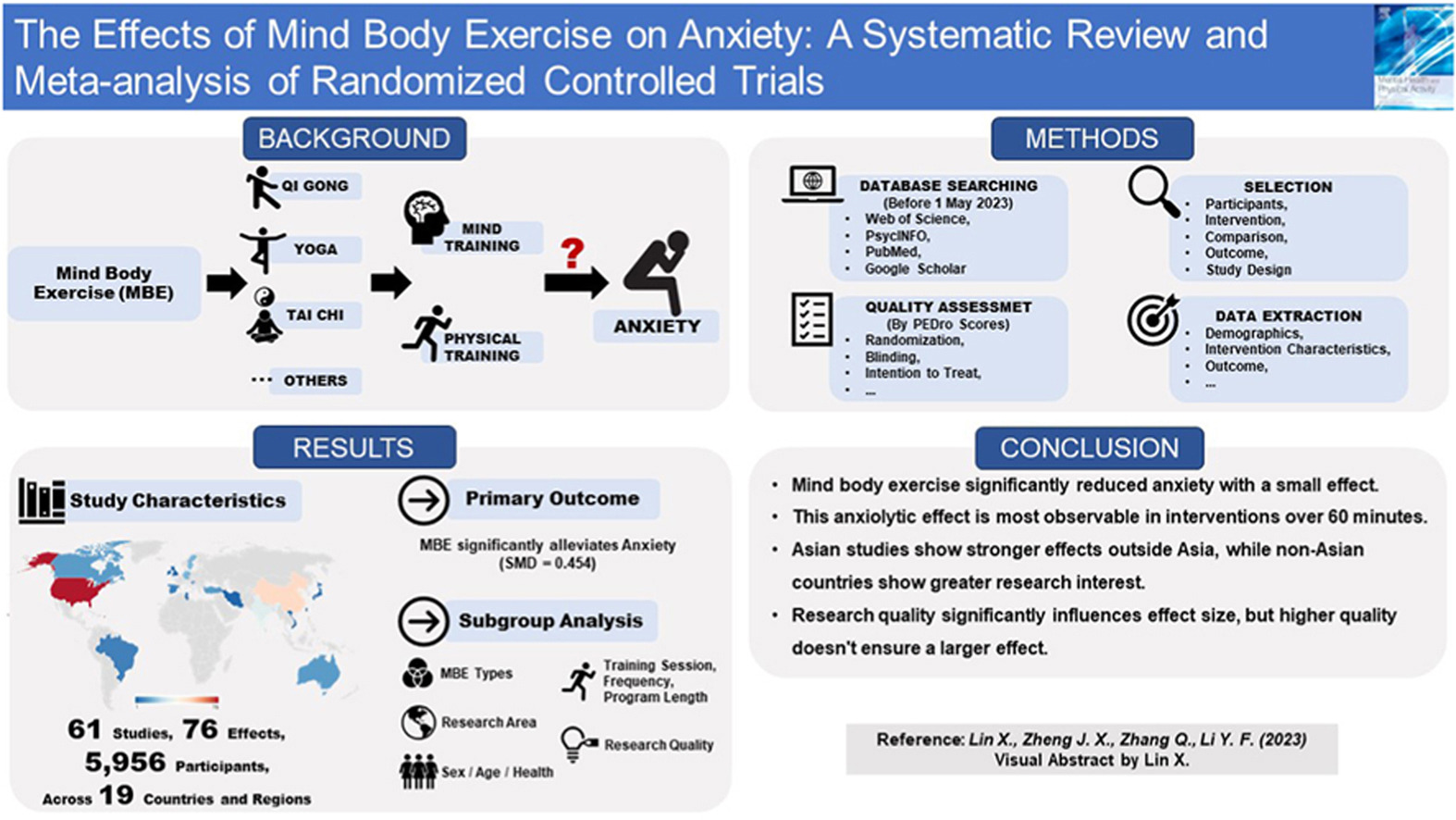

The article we’re looking at this month comes from the journal of Mental Health and Physical Activity. A summary of the abstract is as follows:

- “Mind body exercise (MBE) training significantly reduced anxiety with a small effect.

- This anxiolytic effect is most observable in interventions over 60 min.

- Research quality significantly influences effect size, but higher quality doesn’t ensure a larger effect.”

The presents analysis reviewed 61 studies and found a SMD (average deviation from the mean across all studies) of 0.454 (p < 0.001). That means the average effect was a little less than one half of one standard deviation.

At a minimum this is very helpful information to support adjuctive interventions. It also doesn’t tell the whole story as with other acclaimed cure-alls — e.g. “food is medicine”, “diet fixes everything”, “calories in, calories out”, etc.

“Moreover, compared to traditional therapy alone, MBE combined with it can lead to a better experience of quality of life or a lower level of depression and anxiety.”

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2024.100587

There appears to be a participation bias, where “Asian practitioners are considered more experienced.” That means that stress, or tolerating di-stress, is a skill and living with it requires practice. Skills are the antithesis of “pills and potions” yet oftentimes we expect similar short-term immediate gratification; which is somewhat counterintuitive to the entire process.

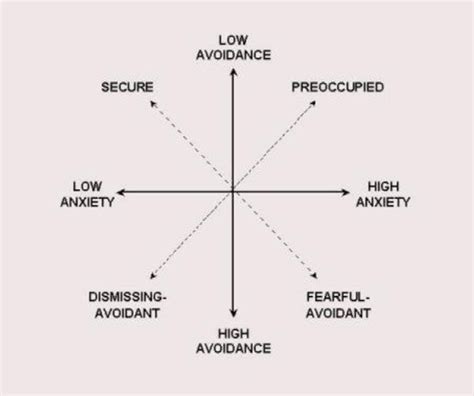

Figure 1. Attachment graph demonstrating the dimensions of avoidance and anxiety, from the Experiences in Close Relationships -Revised measure (ECR-R; Fraley, Brennan, & Waller, 2000): https://internal.psychology.illinois.edu/˜rcfraley/attachment.htm

The “preoccupied” attachment quadrant above is sometimes also called the “anxious” quadrant / attachment style. Without giving medical / clinical advice to any reader, suffice to say that it may be helpful to consider moving in the opposite direction of one’s identified attachments style — which, for the record, is not universal among all of one’s relationships.

Since we are talking about anxiety today, the attachment styles prone to high anxiety are fearful and preoccupied, the difference being that one is also prone to avoidance (fearful).

One model of anxiety is that it is a cognitive function that fixates on the future, specifically things that haven’t happened yet, and ironically this robs us of the opportunity in the present to prevent those things from happening or to be able to prepare to respond accordingly.

With that in mind, the antithesis, or in this case perhaps a balancing force, to a cognitive function (like anxiety) may be to “get out of our head.” In practical terms that may mean engaging in something emotional, but more often than not it means doing — or getting into (engaging) your body / physicality.

On the transverse, if our tendency is to avoid a problem (feeling, or situation), then a likely solution may be to move ourselves towards it — though not recklessly as this is the plight of the preoccupied attachment style.

From our study in review:

“Mind-Body Exercise (MBE) includes physical activity components, and the anti-anxiety effects of physical activity have been extensively verified. Whether MBE can bring additional anti-anxiety effects in addition to physical activity alone is still questionable…”

To bring things full circle, consider that physical activity alone also likely won’t “cure” all your anxious problems.

“An athlete’s drive can push those who aren’t familiar with principles of physiology to unintentionally create anxiety patterns that worsen with training.” ~ The Uneasy Athlete, by Shift Adapt

Remember that the observed effect size in our review study had strong statistical significance — which means the results were very unlikely a chance occurrence. However, the effect size was small, less than one half of one standard deviation. Recall from your basic statistics course that on a normal distribution (“bell curve”), almost 68% of subjects fall within (+/-) 1 standard deviation of the mean (mathematical average).

If one standard deviation (SD) gives us about a 34% boost or handicap, then 34 * 0.454 is about ~15%. We could then guesstimate that MBE reduces anxiety by about 15%. That’s not bad at all.

In fact, for most people with mild anxiety, a 15% change may be all the intervention they need and much to the point of the reviewed article, a savvy clinician could implement these strategies without prolonging treatment.

By contrast, however, a 15% reduction may still leave you at a critical level if your anxiety is “severe.” Most of the time, this is who I’m seeing in clinic. For what it’s worth though, it is the responsibility of an individual to know when to ask for help (when 15% is enough help or not), and it is also incumbent on treating professionals to seek out best practices to treat those they’re serving sans the rigid limitations of specialization and “traditional” modalities.

Discussion continued below…

Lin, X., Zheng, J., Zhou, Q., & Li, Y. (2024). The effects of mind body exercise on anxiety: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 100587. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mhpa.2024.100587

I’ve worked with and been around a lot of hard-chargers, pipe-hitters, and so called “Type-A Personality” (ref.) folks. Some of my therapy clients, whether they’re athletes or veterans, and the majority of the athletes I train, fall into this category. You might even say that I do as well.

For these people, going harder or doing more usually isn’t the problem. In fact, it’s almost certainly antagonistic to the problem.

For example, there’s a positive correlation between substance abuse and high-intensity exercise (ref.). That’s not to say that high-intensity exercises leads to drug use, but it is to say that many of these types of people (CEOs, operators, professional athletes, etc.) are always looking to maintain a hypo manic state — hustle and grind 24/7.

For NCAA Division 1 athletes, over 15% of men have more than 10 drinks when they do drink, alcohol, and almost 40% have more than 5. These numbers increase across Divisions II and III (ref.). The effects are less for women, but similar in proportion.

Shift Adapt has an outstanding webinar, The Uneasy Athlete, that goes into great detail about this process. I’ve written about it many times before, to the tune of:

“…maybe you don’t need an ice bath and a foam roller, and a sauna, and a massage, and (insert trending thing on social media)… maybe you need to touch grass, breathe, and go to bed earlier.”

There can be some pretty low-tech interventions to this process. Yes, we can get all sorts of complicated with different breath protocols, in/under water, in saunas, with and without movement, etc.

Again, more or more complicated probably isn’t the answer most people reading this need. For that matter, it’s not the answer for our perpetually tired but wired (ref.) culture.

Simply walking with controlled or intentional breathing can have a positive impact on exercise tolerance and stress (ref.), that is, decreasing sympathetic nervous system (SNS) activity and increasing parasympathetic (PNS) activity.

If you’re looking to utilized mindfulness practicies (including meditation and breathing), here’s a summary of what I’ve learned over the past year or so:

Consistency trumps intensity. The immortal guidance of Dan John is “a little bit, often, for a long time.”

Down regulation typically involves:

- Awareness / Attention / Intention

- Slowing respiration rate (fewer breaths per minute)

- Adding pauses at the top of the breath cycle

- Extending exhales

- Nasal vs. mouth breathing

The process should be enjoyable, that is a feeling of recovering and relaxing, rather than another stressful “micro-training session.” Though, in truth, recovery is an attribute that needs trained more than any other.