Do Humans Have a Metabolic Exercise Limit?

Gonzalez, Journal of Advanced Nutrition, May 2023, physical activity, energy expenditure

Austin Haedicke

1795 Words | Read Time: 8 Minutes, 9 Seconds

2024-04-24 06:01 -0700

Calories-In-Calories-Out (CICO) is the tried and true recipe for weight loss, right? You need to “burn” more than you consume, right? You’re either at a deficit or a surplus, anabolic or catabolic, right?!

It turns out that “The available evidence indicates that in many scenarios, the effect of increasing physical activity on TEE will be mostly additive although some energy appears to “go missing” and is currently unaccounted for. The degree of energy balance could moderate this effect even further.” (ref.).

To make matters even more confusing, we have headlines like this from The Daily Mail: Too much exercise can kill you - especially if you’re a white man: Study finds 7.5 hours a week of fitness DOUBLES your risk of heart disease.

The Daily Mail, and other claims about “fitness being Fascist” and “drinking milk supports White Supremacy”, are outside the scope of my review here. However, keep this 7.5 hours of exercise figure in mind. As we’ll get to, if someone is scorching 2.5x their BMR in only 7.5 hours of exercise per week, then I will concede that they are putting some outrageous stress on their arteries and body as a whole.

Total Energy Expenditure (TEE) equals non-behavioral / resting metabolism (RMR) plus behavioral expenditure like diet-induced thremogenesis (DIT) and “skeletal muscle force production” (AEE). Physical activity (PAEE) is a subset of AEE.

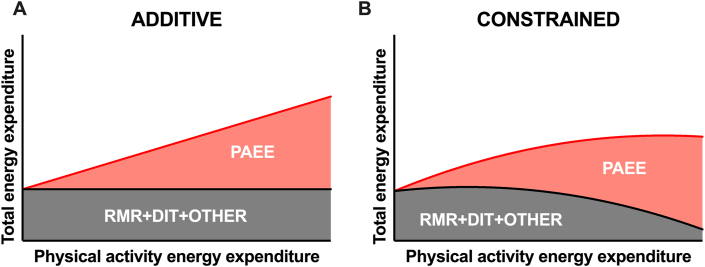

The article in review compares an additive versus constrained energy model. The former implies that there is a consistent basal energy consumption that our body needs that does not vary as physical activity increases. The later, constrained, model states that there are compensatory mechanisms with in the body that will alter how energy is used; particularly in extreme conditions.

Support for the constrained model came after a cross-sectional study of the Hadza (N=32) which was followed up by a study of 332 men from 5 locations / populations.

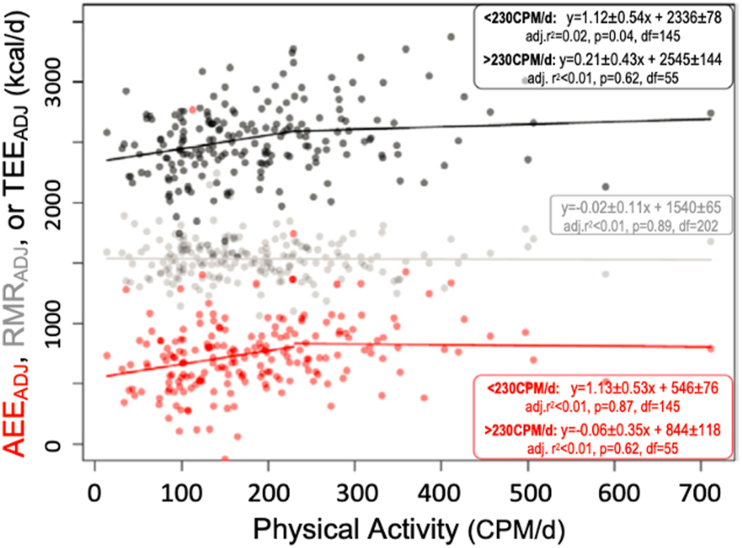

“Across the whole sample, a positive linear relationship was reported between accelerometer counts and TEE up to a proposed threshold of ∼230 counts per minute per day (CPM/d), but above this level, additional accelerometer counts did not predict TEE.”

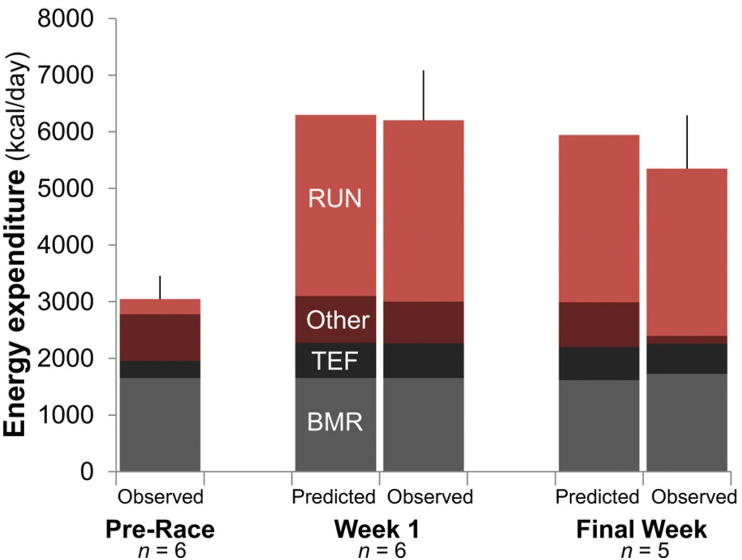

During a ~5,000 Km race event, involving running 6 days / week for 20 weeks, during the first week of the race, participants in “Race Across the USA” hand an energy expenditure of ~6,000 calories / day. However, in the final week there was a notable difference in TEE between predicated and observed models. This was attributed to a decrease in non-exercise physical activity.

Across both models there are notorious difficulties in monitoring both movement, energy consumption, and virtually every data point in this review — hence my former criticisms of the CICO model needing a bubble suit and team of PhDs surrounding you 24-7 to be accurate.

Further,

“Hip accelerometry explains only 6 to 16% of the variance in AEE derived from DLW and 30% of the variance in measured energy expenditure during a battery of physical tasks.”

TEF (thermic effect of food) is rightly pointed out as not being consistent between macronutrients, “but even with accurate diet data, the range within each macronutrient is still considerable, as some variance in TEF is due to the interindividual differences in the postprandial handling of nutrients, and others can be because of food form and / or degree of processing.”

What that means is that the more metabolically efficient we are, the more we can afford to “off gas” calories (energy) as heat (for example) rather than using so much for vital immune function if we were to be sick.

The article goes on to discuss statistical errors such as “regression dilution” and “spurious correlations.” For our purposes here, let’s set up a simple ratio to explore where the wheels fall off.

Let’s say that at 175 lbs, I eat about 3,500 calories / day. If RMR and AEE were held consistent (big ifs) and I wanted to get down to, say 164 lbs, then (3,500 * 164 ) / 175 = 3,280. However, if you recall my previous post on getting down to 5.5% body fat, when I did indeed weigh 164 lbs, I was only eating about 2,400 calories / day.

The CICO model assumes about 3,500 calories / lb of bodyweight for net loss / gain. The previous cut took about 12 weeks to lose 13 lbs. At the start I weighted 177 lbs and was eating ~3,300 calories / day. To lose 13 lbs. I should have needed a net deficit of 45,500 calories (3,500 * 13). Divided by 84 (12 weeks * 7 days) that’s a daily deficit of 541 calories. 3,300 - 541 = 2,759. This is still notably different from what I actually needed to do to achieve the results I got.

Even if we compare the start and end points…

- 3,300 calories / day at 177 lbs.

- 3,500 calories / day at 175 lbs.

- 2,400 calories / day at 164 lbs.

… we see that there is not a linear correlation.

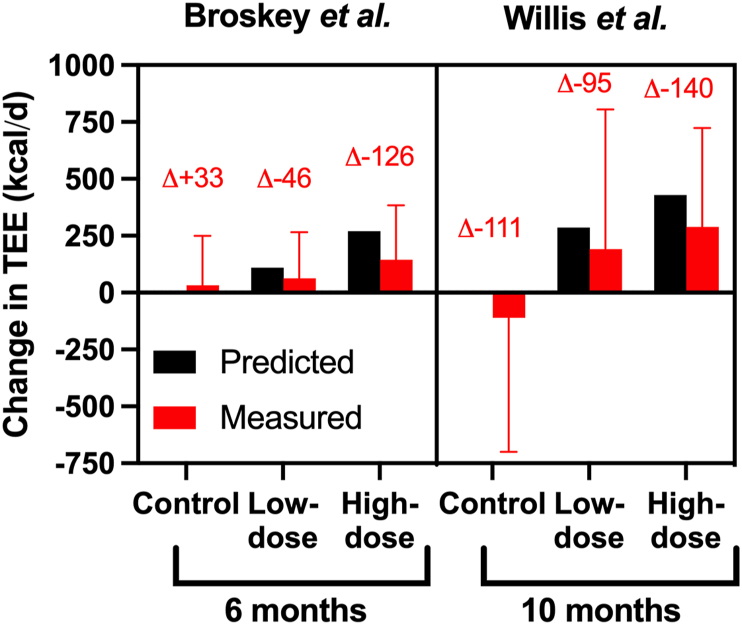

“Predicted and measured changes in TEE from 2 randomized controlled trials of increasing exercise on TEE [50,51]. Each demonstrate some evidence for compensation because the measured increases in TEE are less than the predicted increases. Delta values represent the difference between predicted and measures TEE. Data are means ± SD.”

My examples also illustrate the authors’ points regarding energy balance versus energy expenditure. “When in an energy deficit, RMR can decrease greater than would be predicted by the loss of (fat free mass).” Additionally, “When people increase physical activity to very high levels, it is possible that energy intake does not match expenditure, and thus an energy deficit is created, thereby reducing RMR and producing apparent constraint.”

In the simplest summary, our body is amazing! It appears to shift energy (consumed) to all kinds of processes as it sees fit; whether that’s restoring tissues, ramping up immune function, or simply producing heat.

The article concludes that “there is little evidence to support the extreme constrained model proposed as ‘The bottom line is that your daily (physical) activity level has almost no bearing on the number of calories you burn each day’.”

We may need the pendulum of physical activity to swing pretty far (in either direction) to see the efficacy of a constrained energy model. Most Americans aren’t even “exercising” 20 minutes per day, so it’ makes sense that that “almost no exercise” has “almost no bearing” on the calories you burn each day.

However, what happens when we extend our daily energy expenditure to 2-3x our BMR?

Discussion continued below…

Gonzalez JT, Batterham AM, Atkinson G, Thompson D. Perspective: Is the Response of Human Energy Expenditure to Increased Physical Activity Additive or Constrained? Adv Nutr. 2023 May;14(3):406-419. doi: 10.1016/j.advnut.2023.02.003. Epub 2023 Feb 23. PMID: 36828336; PMCID: PMC10201660.

For support of the original review, let’s also take a look at a 2019 article in Science Advances titled Extreme events reveal an alimentary limit on sustained maximal human energy expenditure.

The most relevant part, from the abstract, states:

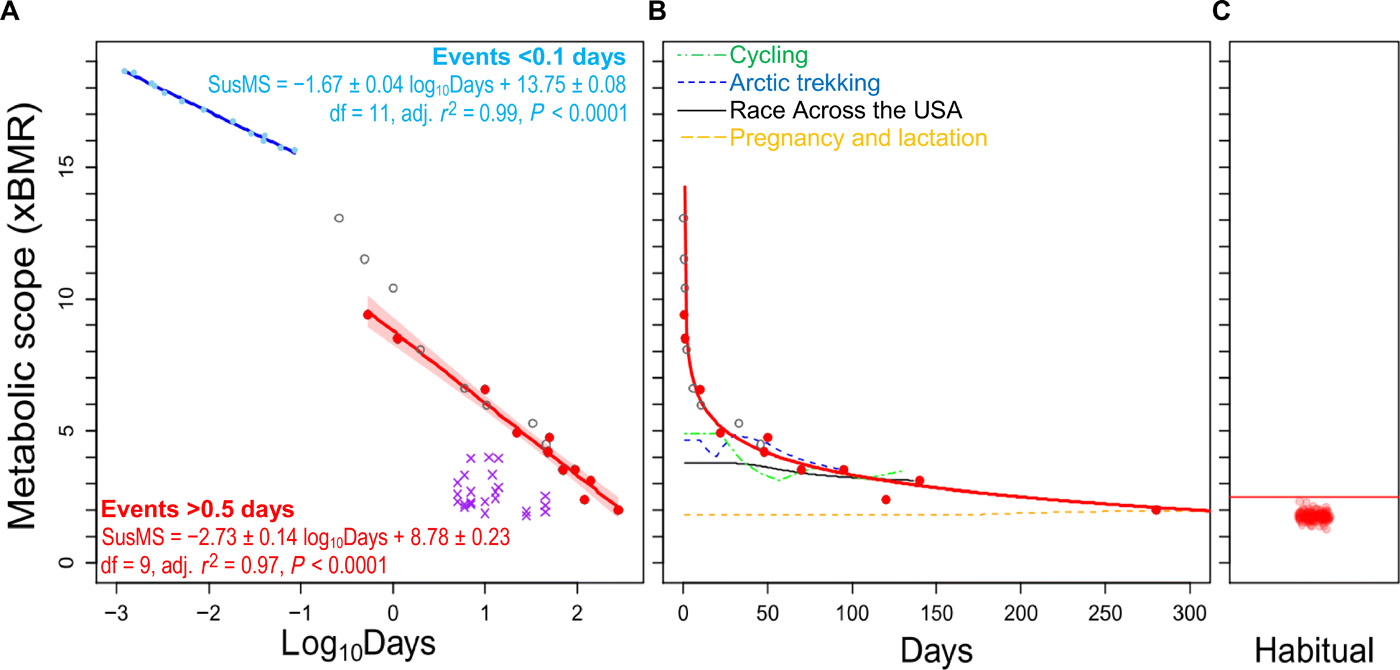

“We compiled measurements of total energy expenditure (TEE) and basal metabolic rate (BMR) from human endurance events and added new data from adults running ~250 km/week for 20 weeks in a transcontinental race. For events lasting 0.5 to 250+ days, SusMS decreases curvilinearly with event duration, plateauing below 3× BMR. This relationship differs from that of shorter events (e.g., marathons).”

The support article notes a scope of 11-hour traithalons and 25-hour ultramarathon athletes expending 8.5x - 9.4x BMR on the days of competition. Expanding on the abstract, the authors write “The increment of expenditure above 2.5× BMR cannot be met with additional intake and therefore cannot be sustained indefinitely.”

Now I’m wondering about Michael Phelps and those french fries and milk shakes and if you can “outwork” a shitty diet? The short (sighted) answer seems to be “yes” — for a couple days, but not indefinitely.

The authors continue to note that:

“…humans around the globe display remarkably similar metabolic scopes of ≤2× BMR during daily life, regardless of differences in activity and lifestyle.”

Just to have some numbers to work with, I plugged my height, weight, and age in to a BMR Calculator which, depending on the method, suggested my BMR as 1,700 - 1,800 calories / day.

Using the 2x modifier would bring me to 3,400 - 3,600 calories / day, which is pretty damn accurate, and something I sustain on a persistent basis. If we start to reach towards the proposed upper limit of 2.5x BMR then I’d be looking at 4,200 - 4,500 calories per day.

Remember that 7.5 hours of exercise figure from The Daily Mail? Let’s do some quick math to reiterate the absurdity of that hypothesis.

- 3,500 calories (output) - 1,800 calories (BMR) = 1,700 calories (PAEE)

- 7.5 hours of exercise (per week) / 7 days (per week) = 1.07 hours per day

- 1,700 / 1.07 = 1,588 calories (total during exercise)

- 1,800 / 24 = 75 calories (hourly BMR)

- 1,588 - 75 = 1,513 calories of output / hour of exercise

If anyone reading this has hit 1,500 calories of output / hour on a daily basis, for more than a week, while doing anything other than sitting on the couch for the rest of the day, please let me know.

16,000 calories on a day you do an 11-hour triathlon? Totally reasonable. An “average white man” doing a triathlon every day in perpetuity? Well, here’s looking at you Goggins… I just ask that you ask him (because he’s given the answer) what those types of endeavors have cost his body and, more importantly, if it was worth it. Also note, that just because the answer was one way for him, certainly doesn’t mean it will be for you or me.

I can tell you from experience that 5,000 calorie days aren’t rare for me in the summer, maybe one / 2 weeks. However, that’s quite illustrative of the support article we’re looking at. Yes, on those days (and those days only) it feels like I could scarf down rice and potatoes, and maybe even bread(!), and “feel fine.” But, very much to the point of both reviewed articles, those conditions are rare; certainly not a daily or even weekly event.

There could be all kinds of directions to go with a budgeting metaphor, for energy consumption and monetary bills / expenses. However, I’ll settle on the recurring fact — that’s thrown in my face every post-30 birthday — that you cannot buy fitness (physical output) on credit; lest you’re willing to pay an absorbent interest rate (e.g. injury, maybe even early death — thanks Daily Mail).

It also means that everyone pays sooner or later. We can add pressure and / or we can build a bigger sink.